It was around the Eighth Century. Scotland and Ireland were on the frontier of the Christian world, and with the fall of the Roman Empire, Christian influence on the culture began to wane. It was the monastery system which preserved and protected the tradition. In scriptoriums, monks copied and illuminated sacred texts of the faith.

On the isle of Iona off the coast of Scotland, a group of monks created a set of the four gospels based on the Latin text of Jerome. In a time before moveable type, the monks went to great lengths to create this series of the four gospels. They say that it took the hides of 185 calves to make this book.

The artwork is exquisite and detailed as the monks tried to bring insight to the text. It also was culturally expressed. The monks used techniques and subjects common to Celtic artwork to illustrate the gospels. It is a great example of how Christians try to use the gospel to redeem the culture around it.

The artwork is exquisite and detailed as the monks tried to bring insight to the text. It also was culturally expressed. The monks used techniques and subjects common to Celtic artwork to illustrate the gospels. It is a great example of how Christians try to use the gospel to redeem the culture around it.

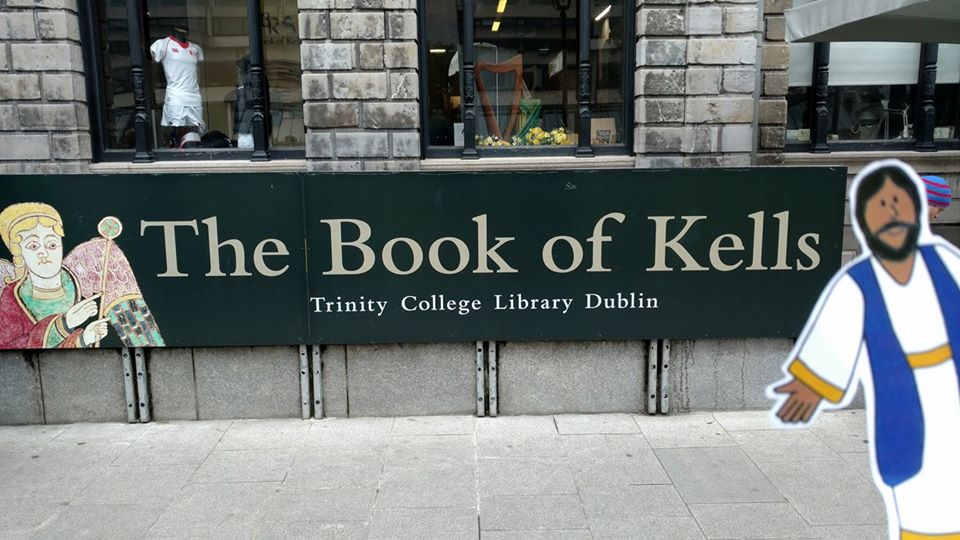

Due to Viking attacks on the Iona, the monks moved the book to a monastery in Kells, a small town in County Meath of Ireland. Hence the book became known as the Book of Kells.

Eventually, the Book of Kells made its way to Trinity College in Dublin where the library displays a different page each day. The book has been placed under special protections, and no visitor can take a picture of any of the pages. Nonetheless, the Book of Kells remains an amazing sight. I appreciate the artwork, but I have even more appreciate the love and dedication to the Scriptures.

We sometimes call this period of time, the Dark Ages, but if it wasn’t for monks like those at Iona and Kells, the age truly would have been dark. They believed that preserving the wisdom and truth of the past ensured a bright future.

Every major reform movement of the Church has begun with a look to the Scriptures. I would argue that the challenge we face today would best be addressed by taking the Scriptures as seriously as did that group of monks on the edge of an empire.

There is an old story about the theologian who is asked for a proof of God’s existence. The theologian says, “I don’t have a proof, but I do know a lady in Connecticut.” In other words, there may not be a mathematic proof with absolute certainty, but there are witnesses, people who are in relationship to God.

There is an old story about the theologian who is asked for a proof of God’s existence. The theologian says, “I don’t have a proof, but I do know a lady in Connecticut.” In other words, there may not be a mathematic proof with absolute certainty, but there are witnesses, people who are in relationship to God. On Christmas Day 2008, our family packed the last of our things and left Texas to come to Philadelphia. I became the pastor of the Ardmore Presbyterian Church on the heels of this congregation’s centennial. I was and am excited to become a part of APC’s next century. I knew that my time here would be challenging, but I also knew that this congregation was willing to be supportive of their pastor. When I came, the church offered me a three-month sabbatical after serving seven years. They knew that after a season, it is necessary for a pastor to reflect, to rest and to retool for the next series of challenges. I am grateful for that foresight.

On Christmas Day 2008, our family packed the last of our things and left Texas to come to Philadelphia. I became the pastor of the Ardmore Presbyterian Church on the heels of this congregation’s centennial. I was and am excited to become a part of APC’s next century. I knew that my time here would be challenging, but I also knew that this congregation was willing to be supportive of their pastor. When I came, the church offered me a three-month sabbatical after serving seven years. They knew that after a season, it is necessary for a pastor to reflect, to rest and to retool for the next series of challenges. I am grateful for that foresight.

Every four years, presidential candidates from the political parties prance and preen before the voters in primary politics. Invariably, these efforts seem to collide with the church’s calendar. Many followers of Jesus are now observing the season of Lent. At the same time, Christians are examining themselves, seeking repentance and humility, the airwaves are filled with men and women claiming to be the best hope for America.

Every four years, presidential candidates from the political parties prance and preen before the voters in primary politics. Invariably, these efforts seem to collide with the church’s calendar. Many followers of Jesus are now observing the season of Lent. At the same time, Christians are examining themselves, seeking repentance and humility, the airwaves are filled with men and women claiming to be the best hope for America. In this day and age, our families are strewn around the world. Getting everyone physically together in one place is challenging. As a result, when it happens, it’s a big deal. There will be tears, laughter, hugs, and kisses. And the family will share stories.

In this day and age, our families are strewn around the world. Getting everyone physically together in one place is challenging. As a result, when it happens, it’s a big deal. There will be tears, laughter, hugs, and kisses. And the family will share stories. In high school, I discovered a passion for mathematics. I was never thrilled with simple computation. Arithmetic bored me. However, starting with geometry I fell in love with mathematical proofs. Starting with simple truths and universal principles, I derived airtight, logical arguments about the way angles, circles and parabolas behaved. I found power, truth and even beauty in logical arguments. There was great satisfaction to reach the end of a geometric proof, “quod erat demonstrandum.”

In high school, I discovered a passion for mathematics. I was never thrilled with simple computation. Arithmetic bored me. However, starting with geometry I fell in love with mathematical proofs. Starting with simple truths and universal principles, I derived airtight, logical arguments about the way angles, circles and parabolas behaved. I found power, truth and even beauty in logical arguments. There was great satisfaction to reach the end of a geometric proof, “quod erat demonstrandum.” In the liturgical calendar, the Sunday after Pentecost is known as Trinity Sunday (May 31). On that Sunday, the Church celebrates the Trinity — God as three persons, yet God being one. Although the word, “trinity,” does not appear anywhere in Scripture, the doctrine has been essential to the Christian faith. Jesus himself commands his disciples to use the formula, “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,” in baptisms (Matthew 28:19). As a result, as we reflect on the beginnings of our life in Christ, we should be drawn to examine the relationship of these three persons.

In the liturgical calendar, the Sunday after Pentecost is known as Trinity Sunday (May 31). On that Sunday, the Church celebrates the Trinity — God as three persons, yet God being one. Although the word, “trinity,” does not appear anywhere in Scripture, the doctrine has been essential to the Christian faith. Jesus himself commands his disciples to use the formula, “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,” in baptisms (Matthew 28:19). As a result, as we reflect on the beginnings of our life in Christ, we should be drawn to examine the relationship of these three persons.